Researchers are learning to use a concrete four-principle framework to design experiments that are better at catching unexpected discoveries. This could help build a more fruitful research culture for all.

The history of science is filled with legendary "happy accidents," from penicillin to the microwave oven. These breakthroughs are often attributed to luck. But Prof. Keisuke Goda (University of Tokyo) and his team argues in a recent paper in Progress In Electromagnetics Research(Vol. 184, 14-23, 2025;doi:10.2528/PIER25100702)[1], entitled "Serendipity Engineering with Photonics: Harnessing the Unexpected in Biology and Medicine," that such accidental discoveries can be systematically cultivated. It introduces "serendipity engineering" — the intentional design of tools and research cultures to make unexpected, yet meaningful findings more likely.

This reminded me of a conversation with a colleague who once chaired the Nobel Prize in Physics committee. He observed that transformative discoveries—the kind that win such prizes — cannot be planned against a project budget for a fixed list of specific equipment. This stands in sharp contrast to funding models that rigidly lock in project parameters and equipment, and which ultimately penalize perceived failure. The paper's central thesis powerfully addresses this tension: some transformative discovery cannot be prescheduled. It argues for the intentional creation of serendipity-engineered environments where unforeseen insights can be not just recognized, but actively pursued.

From "Happy Accident" to Engineered Insight

The paper replaces the vague idea of luck with a concrete four-principle framework:

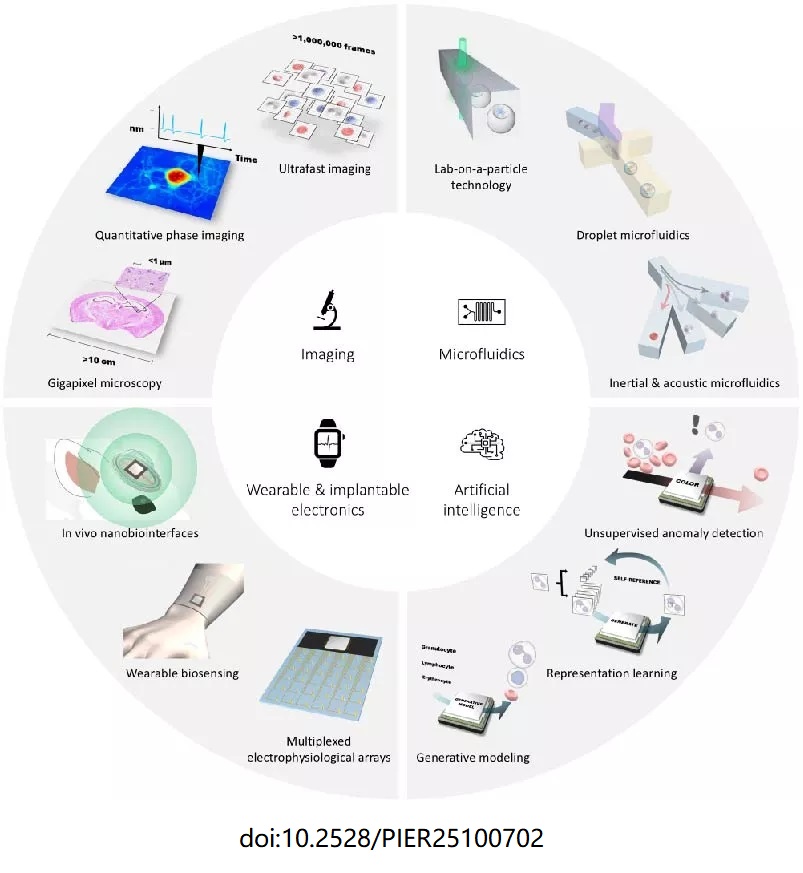

- Make Better Observatories: Utilize advanced tools, such as high-speed, super-resolution, and high-dimensional imaging technologies, to see more of the biological microscopic world, thereby increasing the chance of likelihood of novel discovery.

- Save the "Mistakes": Implement unbiased data practices to ensure unusual signals are not automatically discarded as mere noise or instrumental errors.

- Look for Odd Patterns: Apply AI and new analysis methods specifically designed to spot unusual correlations.

- Foster Open Minds: Cultivate labs and funding that reward curiosity and the pursuit of unexpected trails.

In photonics and biomedicine, technologies such as light-sheet microscopy and wearable biosensors act as these "discovery engines," letting researchers observe life at unprecedented scale and detail. Critically, advanced photonics tools expand the observable space in key dimensions: in speed and data richness (e.g., via AI-enabled snap-shot high-dimensional hyperspectral compressive imaging, which allows for the rapid capture of vast amounts of spectral/chemical and spatial data simultaneously) and in resolution (e.g., via lattice light-sheet microscopy for high spatiotemporal imaging). This allows researchers to "catch" fleeting biological anomalies or rare cellular events that were previously invisible, directly enabling the core tenet of the framework.

A Universal Framework for Discovery

While powerfully demonstrated in photonics, this framework transcends any single field. The core challenge is universal: tightly goal-oriented research can miss the sideways glance that changes everything.

The discovery of the fractal antenna by physicist Nathan Cohen in 1988 perfectly illustrates serendipity engineering outside photonics. His apartment's "no large antenna" rule posed a practical challenge. Inspired by a 1987 lecture on fractal geometry by Benoit Mandelbrot, Cohen approached the new concept with playful skepticism. He wondered if bending an antenna wire into a self-similar fractal shape—as a kind of humorous experiment—could possibly work. His process maps directly onto the four principles: his playful application of fractal geometry expanded the design space; he preserved the anomaly of the working antenna instead of dismissing it; he recognized the odd pattern of multi-band performance that contradicted theory; and he fostered the necessary openness to pursue it despite peers initially dismissing his 1994 paper as an April Fool's joke. Cohen's openness allowed him to recognize and develop this chance finding into a foundational technology for modern smartphones [2].

The principles of expanding observation, preserving anomalies, seeking novel patterns, and cultivating open curiosity are applicable anywhere unpredictable discovery occurs.

Conclusion: Planning for the Unplanned

Prof. Goda and his colleagues offer more than a review; they provide a vital toolkit for 21st-century research. "Serendipity engineering" is the practice of planning for the unplanned. It is the strategic recognition that while we cannot budget for a Nobel Prize, we can—and must—design our science to be more receptive to the brilliant, unexpected insights that ultimately propel all fields forward. Ultimately, embracing serendipity engineering challenges not only how we design experiments, but also how we evaluate research proposals, tolerate 'failure,' and reward intellectual courage. The question for the scientific community is no longer whether serendipity matters, but how systematically we are willing to build it into the very architecture of our research.

References

[1] Kelvin C. M. Lee, Walker Peterson, Fabio Lisi, Tianben Ding, Kotaro Nojima, Hiroshi Kanno, Yuqi Zhou, Hiroyuki Matsumura, Yasutaka Kitahama, Ming Li, Petra Paie, Cheng Lei, Tamiki Komatsuzaki, Masahiro Sonoshita, Dino Di Carlo, and Keisuke Goda, "Serendipity Engineering with Photonics: Harnessing the Unexpected in Biology and Medicine (Invited Paper)," Progress In Electromagnetics Research, Vol. 184, 14-23, 2025.

doi:10.2528/PIER25100702

[2] Nathan Cohen. Fractal antenna applications in wireless telecommunications. Electronic Industries Forum of New England, Professional Program Proceedings, May 1997.